February 28 marks the 70th anniversary of Francis Crick and James Watson’s discovery of the double helix model of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA.

Their 1953 discovery built on the work of many previous researchers including: Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher, who in the late 1860s first identified nuclein/nucleic/deoxyribonucleic acid; colleague Maurice Wilkins; and the unrecognised but vital work of Rosalind Franklin. In 1962, the Crick and Watson, along with their colleague Maurice Wilkins, were awarded the Nobel prize ‘for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material.’

In the 70 years since their announcement, there has been ongoing DNA research, culminating last year in the successful mapping of the complete human genome. The ambitious Human Genome Project, a global collaboration of researchers, identified 92 per cent of human DNA in 2003 (with 400 gaps in the sequence), and in March 2022, the first truly complete human genome sequence was identified.

Early DNA testing or profiling was first used in the 1980s, for crime-solving forensics (with police in Leicester, UK first using DNA to solve a rape/murder case) and for paternity and pre-natal testing. It has become much more accessible, and is now widely used not only in archaeological, scientific and genealogical research, but even used to identify canine culprits fouling apartment complexes. Tennessee-based company Poo Prints maintains a database of dog DNA using cheek swabs taken from pets when their owners move into apartments. The apartment managers can then send samples of unpicked-up faeces to the company to identify the offending canines.

Identifying which owners are not doing the right thing in cleaning up after their pets may be a nice-to-have, but knowing which species are causing damage to aircraft is critical to managing wildlife hazards and informing habitat management and aircraft component design.

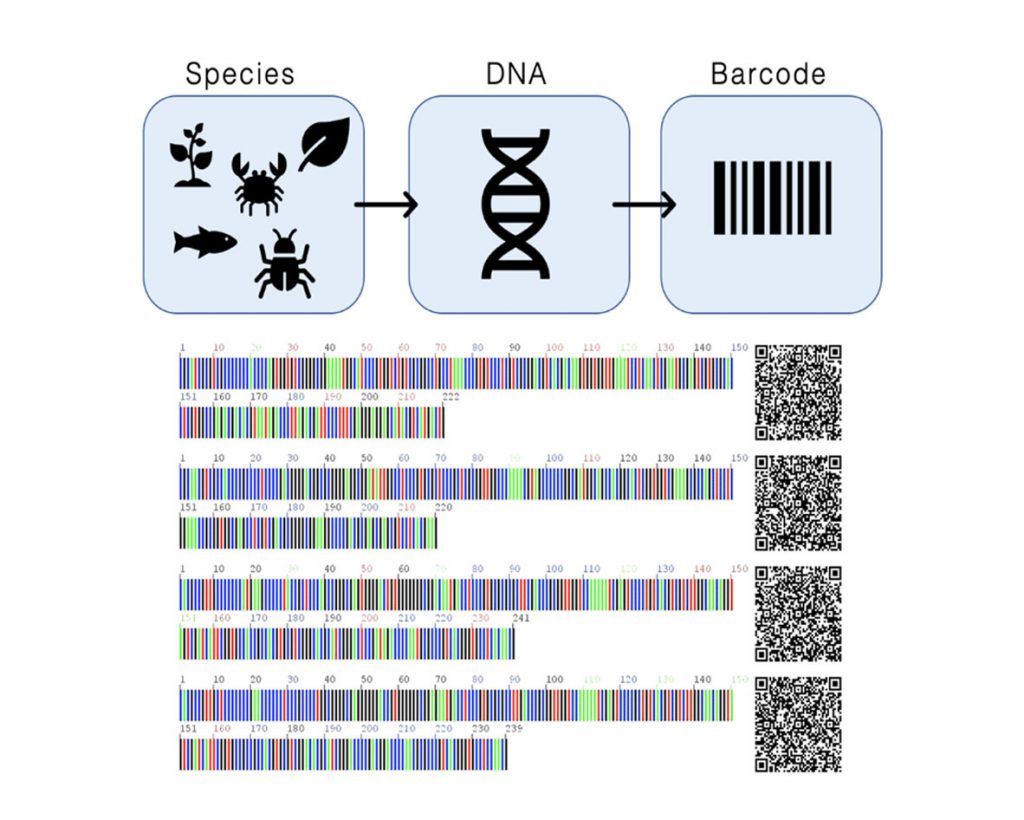

Dr Matthew Lott is a scientific officer with the Australian Museum’s Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics. In a presentation he gave last year during Airport Safety Week, he outlined the history of wildlife DNA-based species ID, and some of the benefits of such testing.

‘Wildlife airstrike statistics are currently strongly biased towards the detection of larger and more easily recognisable species,’ he said. Not only that, but in a quarter of reported bird strikes, physical remains are not good enough for accurate species identification. That’s where DNA comes in.

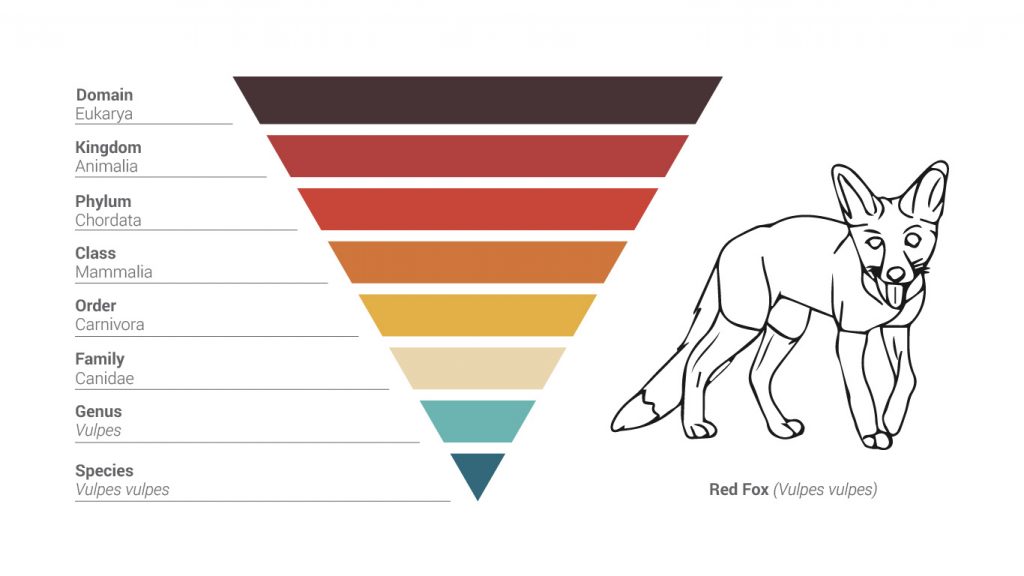

‘In 2003, DNA barcoding was proposed as a standardized method for species identification’, Lott explained. ‘Using DNA-based methods we are able to achieve species-level identifications in 84.36 per cent of wildlife airstrike cases, with 9.02 per cent of DNA-based IDs at the genus level, and only 6.62 per cent of tests yielding no result.’

‘We understand the costs associated with DNA-based species IDs may disincentivise smaller regional aerodrome operators from utilising our services’, he said. ‘We are exploring the possibility of securing external funding to subsidise these costs and encourage further uptake of these services among relevant stakeholders.’

For more information about the Centre’s DNA testing services, contact Airstrike@Australian.Museum